By Andy Churchill & Bryan Harvey

Once again, Amherst is in a fiscal crisis. Spending keeps rising, state aid hasn’t kept pace, federal COVID funds have dried up, and local tax rates are already high.

Again this year, it’s apparent that Amherst’s revenue isn’t enough to support all the services town residents depend upon. So far this has led to discussions of where we can cut costs, pitting various town departments and constituencies against each other in a zero-sum game.

While we should certainly be looking at smart cost savings, we can’t afford to ignore the revenue side of the picture. What options do we have for a strategy that “expands the pie” of available town funds without raising taxes beyond the limitations of Proposition 2½? One option stands out: bring in more net tax revenue by expanding housing.

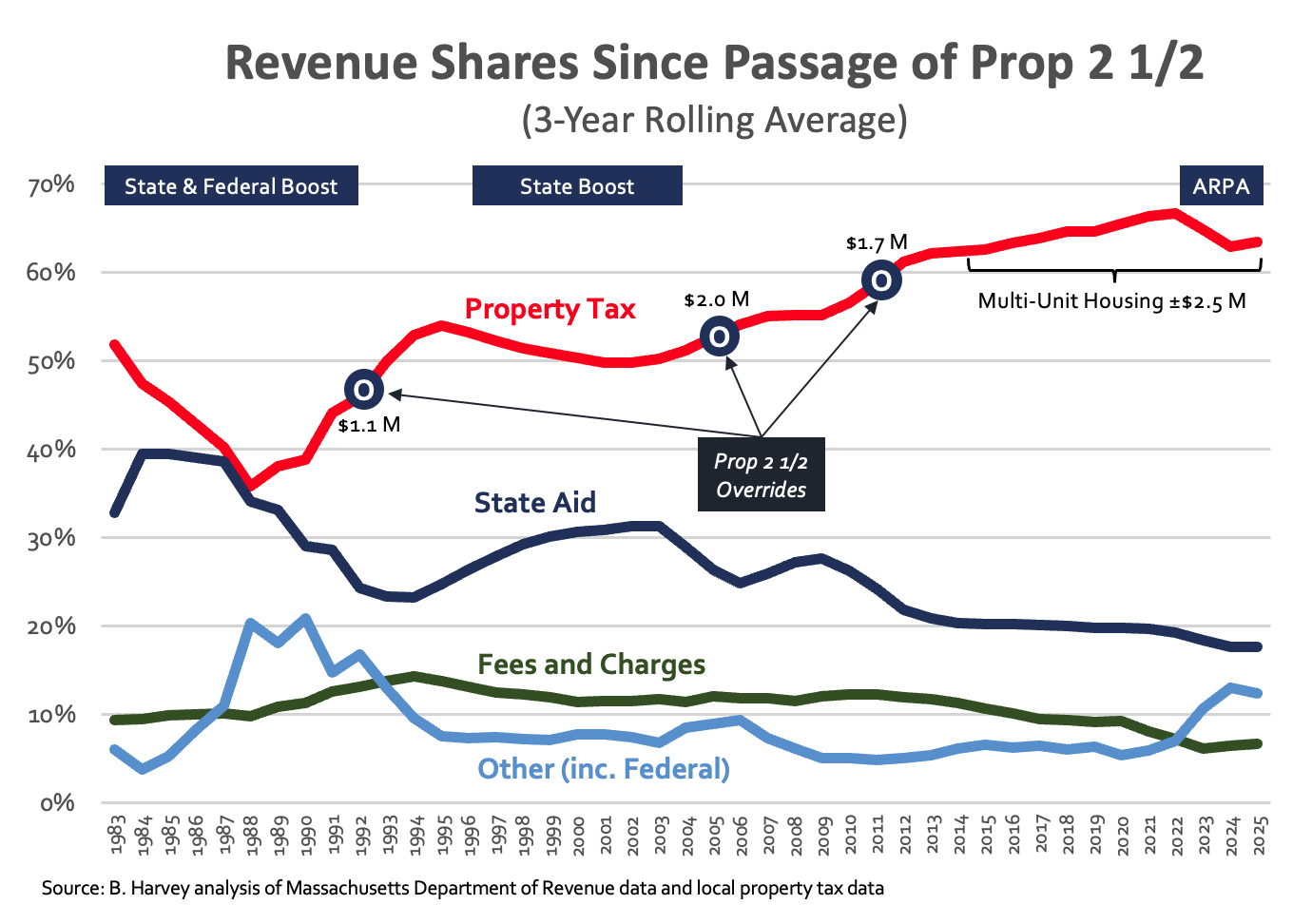

A quick look at where we get our money paints a pretty clear picture: as the share of our budget paid by the state has declined, we’ve had to make up the difference locally.

And the revenue coming from the local property tax consists almost entirely of taxes on people’s homes.

When 88% of local taxes come from residential properties, the gap with state aid translates directly into higher tax bills and rents.

This dilemma is not something new. The first graph above looks all the way back to the passage of Proposition 2½, and it’s clear that — like many other communities — Amherst has looked for ways to go beyond its cap. Roughly speaking, every six or seven years we’ve had to find some way to boost local revenue in order to maintain service levels.

- During the first years of Prop 2½ in the 1980s, the state pumped millions of dollars into local budgets, providing substantial property tax relief.

- But in the 1990s the state put the brakes on local aid, and reliance on the property tax shot up. We had our first Prop 2 ½ override in 1992.

- Then for a while state aid rebounded, and we were able to avoid another override for a dozen years.

- As we moved into the new millennium, however, even though state aid increased, it did not grow as fast as local spending. Reliance on the property tax reached new heights with overrides in 2005 and again in 2011. It was a grim pattern: would we need overrides forever?

The answer turned out to be somewhat surprising. Beginning in 2014 major new multi-unit housing—primarily to accommodate growth in UMass enrollment—began to appear for the first time in more than forty years.

Whatever else one might say about them, those projects pay a lot of property tax, more than $2 million worth, each year (about what we would typically look for in a Prop 2½ override).

Here is the current annual tax revenue from a selection of these recent housing projects:

| Annual Tax Revenue | Property | Year Built |

| $331,531 | Olympia Drive | 2014 |

| $303,654 | 1 East Pleasant | 2017 |

| $214,348 | Kendrick Place | 2018 |

| $112,726 | 70 University Drive | 2019 |

| $305,293 | Aspen Heights | 2020 |

| $145,736 | University Drive South | 2021 |

| $277,851 | 11 East Pleasant | 2022 |

| $191,600 | Southeast Commons on South East | 2024 |

Without them (and temporary ARPA funding from the federal government at the height of the pandemic), we’d either be going to the voters again for tax overrides or seriously reducing budgets for schools and services (not just arguing about how much to increase).

So Amherst has demonstrated its ability to bring in new revenues by expanding housing, especially through denser development. Can we find other opportunities along these lines?

This strategy is about much more than revenue, of course. Housing in all its dimensions—supply, affordability, impacts on neighborhoods—represents a central challenge for our community. Student-driven housing is one option, not a prescription, for revenue growth.

Let’s consider some other options:

- Senior housing. It is evident that a great deal of our housing capacity is currently occupied by long-time residents (like both of us) who want to remain in the community but see few options beyond staying in the family home. Could we change that, by encouraging more senior housing, and expand net revenue while simultaneously opening up capacity for new generations?

- Young professional housing. What about younger professionals who want to live in a community like ours but are past their “student” housing days? What could we offer them?

These kinds of “win-win-win” opportunities can serve our whole range of housing goals: 1) generate significant amounts of spendable revenue, 2) support affordability by expanding overall supply, and 3) do so without negative impacts on established neighborhoods.

How can we plan for and support these types of opportunities? Here are a few thoughts:

1. Make revenue generation through housing development a priority. We should not be pursuing development for its own sake, but we also can’t overlook its capacity to help our community fund its values and aspirations. Potential projects need to be evaluated in terms of how much they can help by generating net revenue available for town services.

2. Set revenue targets to meet town goals. A few rough scenarios can move these ideas from an abstraction to a real set of choices. For example, at our current rate of spending, how much new revenue do we need in order to avoid overrides? Or to actually reduce taxes? Or to address long-neglected infrastructure challenges? We don’t need a hundred projects: we need a few good ones that can meet identified community goals.

3. Build a pro-housing coalition. Whether you’re a parent concerned about school funding, a senior with more house than you need, or anyone who has wondered how we’ll fix all our bumpy roads, your voice matters. Pro-housing coalitions are springing up across the Commonwealth in favor of sensible, revenue-generating housing development and the appropriate zoning and permitting that supports it (see Abundant Housing Massachusetts for examples). We should have one here, too.

The key is to decide what works for us and what it will take to get there. We can increase revenues without raising taxes. And we can do so while relieving pressure on housing costs. Let’s work together to build more housing.

Andy Churchill is a member of the 2024 Charter Review Committee and served as chair of the 2016-2017 Amherst Charter Commission. He also served on the Amherst School Committee from 2004 to 2010.

Bryan Harvey served as chair of the 2001-03 Amherst Charter Commission. He also served on the Amherst Finance Committee from 1981 to 1991, and on the Amherst Selectboard from 1991-2001. He is married to Town Councilor Lynn Griesemer. This post reflects his own perspective.

Discover more from THE AMHERST CURRENT

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You make many good points for consideration. I’d like to throw into your think tank the revenues that could be derived, and also fairness achieved, by creating a PILOT for commercial rental housing. It’s the 2nd biggest industry in Amherst, after higher ed. State law does allow a municipality to establish a commercial real estate tax rate, within the bounds of Prop 2 1/2, but a PILOT might be easier. It could be based on the actual costs to the town of having UMass, Hampshire College, and Amherst College. This would be comparable to a fee on gas that was the true cost of fossil fuels. A PILOT is a user tax, versus having the general population subsidize the wear and tear of our road, our police and fire, our water supply, and more. This is nothing against students or higher ed, it’s just a matter of who pays for that. The owners of Amherst’s commercial rentals are a mix of local heroes and faraway hedge funds, and consider that an owner/occupier of a house in Amherst is paying- in their tax bill -those special costs, not incurred by them. This idea only means that commercial landlords pay their true costs. If that was what gave Amherst increased solvency, it would seem fair and just to me. (note: I have been a commercial landlord, and paid at a commercial real estate rate- which I felt was fair)

LikeLike

Hi, Ira. See my reply to Steve Kurtz, below.

LikeLike

Revenue from UMASS, and the other colleges is limited by the State formula for PILOT. (payments in lieu of taxes). I’m not an actuary or accountant, but assessments on raw land value excluding the improvements (buildings, sewer, water, electric, cable, paving, gardens…) likely results in a loss of many millions of dollars of potential revenue. Maximum pressure should be exerted at the State level to rectify this. Our roads are relatively empty when these institutions are out of session. It’s not just student vehicles, but also trucks for deliveries, normal maintenance work, and contractors doing repairs, improvements, or new construction. Our roads are full of potholes, and other damage from the doubling of our population, and effectively tripling as many full-time residents share a vehicle or are too young or old to drive. A clever cartoonist could produce some biting satire on this topic such as these academic icons set amongst ruined roads.

Steven Kurtz

LikeLike

Thanks, Steve (and Ira). As you both point out, there are many angles to revenue, and we need to be looking at all of them. People have been working on the PILOT/impact front for as long as I can remember, and some progress has been made. We focus on housing here because it is such a huge part of our revenue, and because some elements of it are within our direct influence.

One thing to keep in mind about housing is the way it is taxed in Massachusetts. All residential property — from a tiny house to Puffton Village — is taxed at the same residential rate. Only hotels and such pay the commercial rate. An apartment building’s value for tax purposes can consider its “commercial” activity (e.g. rent income), but the value gets taxed just like a single family home. Just one of the many obstacles on our zig-zag course to fiscal sustainability!

LikeLike

Senior and young professional or grad student housing brings in more taxes than their cost to the town. Hadley is going big on senior housing with relatively high evaluation and no impact on schools. PILOTS would discourage building any more units because rental units are already being taxed on their NOI and Rental Registration, a not insignificant expense for the small landlord. A 200 sf studio registration fee is the same as a four-bedroom rental house which is more likely in need of surveillance.

Not exactly an endorsement to own rental property in Amherst.

LikeLike

Great analysis, Andy and Bryan! The graphs clearly show our fiscal reality – declining state aid and 88% reliance on residential property taxes. The $2M+ annual revenue from recent housing developments proves this strategy works.

With both revenue shortfall and housing shortage, sensible development is essential. Senior, professional, and workforce housing options make particular sense – they generate more taxes than they cost in services while addressing real community needs.

But as Hilda noted, we’ve created real barriers: super stretch codes, rental registration fees, and neighborhood resistance all add costs and delays. From a policy perspective, we also need to consider:

– Infrastructure capacity (water, sewer, roads) and upgrade costs

– Zoning changes needed to enable these projects

– Financing mechanisms for developers, especially for affordable components

– Community benefit agreements (legally binding contracts between developers and community groups that guarantee specific local benefits like affordable units, local hiring, or community facilities) to address neighbor concerns

I’d love to hear from developers: What’s the actual demand for senior/workforce housing? What specific regulatory or financial barriers prevent these projects? Are there policy tools (zoning bonuses, tax incentives, streamlined permitting) that would tip the scales?

We have the data showing housing development works fiscally. Now we need to understand what policy changes will make it happen.

LikeLike

Amherst Current, a town’s residents, with a desperate need for information and analysis that isn’t hopelessly biased, turns its lonely eyes to you.

LikeLike

As I understand it, subject to correction from someone better informed, there is no way for the Town of Amherst to compel the annual provision of income and expense information from these apartment complexes. Therefore, usually, the Town does not get it, from any of them. This came as a surprise to me when I first heard it.

LikeLike