By Bryan Harvey

For the second year in a row, we find ourselves in a contentious battle over the school budget. The Regional School Committee blew past the town’s budget guidelines; the Town Council refused to go along with the School Committee’s plan to allocate costs to the four member towns; and we appear to be moving — again, for the second year in a row — toward some kind of uneasy temporary truce.

Officially, the dispute is about what seem like budgetary arcana: which spending items are put at risk; fractions of percentage points in capital spending; and competing assessment methods. But these are symptoms of a much weightier issue. The wheels have come off our longstanding compact on how to divide the community’s resources. We’ve lost a shared sense of who needs what, and without that, the teeth are breaking off the budgetary gears.

The Narratives

You can see this in the competing narratives offered by various parties. Here are three of the main ones I’ve heard.

Narrative One: Clueless or uncaring local officials are needlessly withholding the funding necessary to preserve minimum acceptable levels of quality in our local schools. The corollary to this narrative is that the community must produce whatever level of funding the School Committee requests, regardless of other impacts. (This characterization is not intended to be hyperbolic; I’ve heard it stated in just about these words by some School Committee members and school advocates.) I call this one the “Prioritize Education” theory.

Narrative Two: We’re in a jam, and it’s a mess, but we don’t know what else to do. So we need to keep on spending the way we’ve been spending, and hope that somehow it will sort itself out. Interestingly, this approach attracts folks with very little in common on the actual spending dispute. The School Committees express it in the form of the “level services” theory of the budget. Some argue that the only way to keep the budgetary peace is to stick with the “equal distribution” deal struck some 45 years ago. Let’s call this the “Stay the Course” theory.

Narrative Three: Our world has changed, and we haven’t kept up. It is way past time to take a step back, reassess our reality, and figure out as a community how to express our values in a financially sustainable way. You can hear elements of this narrative in both quiet corners and formal proposals (for example, in early conversations three years ago between the Town Manager and the then-School Superintendent; in requests by the Town Council for the past two years that the School Committees participate in a joint exploration of these issues; and most recently in a proposal by Amherst School Committee member Irv Rhodes to launch a collaborative review of the regional budget). That none of these initiatives have gone anywhere says a lot about how far we are from serious problem-solving. Let’s call this the “Wake Up and Smell the Coffee” theory.

How can we choose among these conflicting theories, begin to get past the rhetoric, and do the work of “saving our schools” (and everything else that we value)? Let’s go through them one at a time.

Narrative #1: Prioritize Education.

While this can be a tempting reaction to a threatened loss of teaching positions or curricular options, does it really describe the situation?

To me, this is a pretty easy question to answer.

To start, no one is proposing to reduce the school budgets. The debate is over exactly how much faster than inflation spending needs to go.

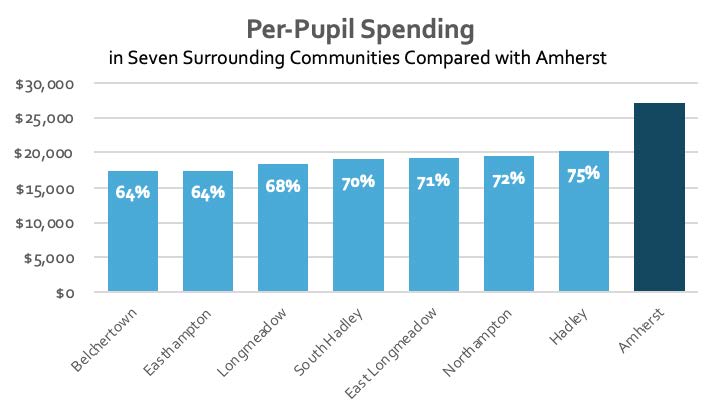

Second, Amherst spends half again as much per student as nearby districts.

Statewide, Amherst nearly leads the league in school spending. If you exclude resort communities with few year-round residents and luxury-home tax bases, Amherst has the tenth-highest school spending in the state. Take out big urban communities — all of which receive more state school aid per student than Amherst — and we move up to #6. Take out Rowe (enrollment of 91) and Erving (215), and we’re #4. Take out MetroWest communities with staggeringly higher property values, and… well, there’s no one left to take out. If spending more than almost anyone else is not evidence of “prioritization,” what is?

As I dug into these data I struggled to come up with a phrase that adequately captures the extent to which the claim that Amherst skimps on education misses the mark. But here’s one to think about: ask the folks in Northampton or Longmeadow if they think they could run a pretty decent school system with an extra $9,000 per student.

But what about the other half of the theory, that we should move money out of non-school services to permit school spending to grow even faster? Here’s what that proposal actually amounts to:

- The whole non-school part of the budget is not available to re-allocate. A whole raft of mandatory payments come off the top, including debt service (most of which is going to a new elementary school); insurance and retirement benefits; and assessments from other governmental entities (like the $1.3 million we’re taxed to run PVTA).

- The dollars that actually can be allocated break down like this: 57% for the schools, 43% for everything else.

- Moving that $900,000 to the 57% does produce another 2%. But stripping it from the 43% forces a 2.6% loss. And the longer this goes on, the worse it gets. After five years of this, the schools would be ahead by 10.8%, paid for by a 14.2% reduction in the allocation for everything else. The difference in dollars at that point? More than $5.5 million annually (roughly the entire Fire/EMS budget, or twice what we spend on DPW).

This does not seem like a durable strategy.

Another proposed “solution” — taking the extra school money from the community’s financial reserves — also fails the reality test, for one simple reason: the solution doesn’t fit the problem. The School Committees are asking for permanent money, a “base” that gets bigger every year. But reserves can only be spent once. At best, using up reserves can delay the moment of budgetary reckoning, but the price of delay is very high: leaving the community (and particularly the schools, which consume most of our discretionary spending) exposed to God-knows-what financial risks are coming to government spending at every level. COVID showed us just how vulnerable we are. Then, the federal government bailed us out. This is not a time to be tempting the fates by performing without a net.

Narrative #2: Stay the Course.

The biggest vulnerability of this theory is that it permits us to close our eyes to the realities we face.

I’ve been a planner all my life. Planning is the process of understanding a situation and taking action that makes sense in that context. If a situation is fairly stable, what we’ve done in the past may work pretty well. But when our situation changes, planning must rise to the occasion.

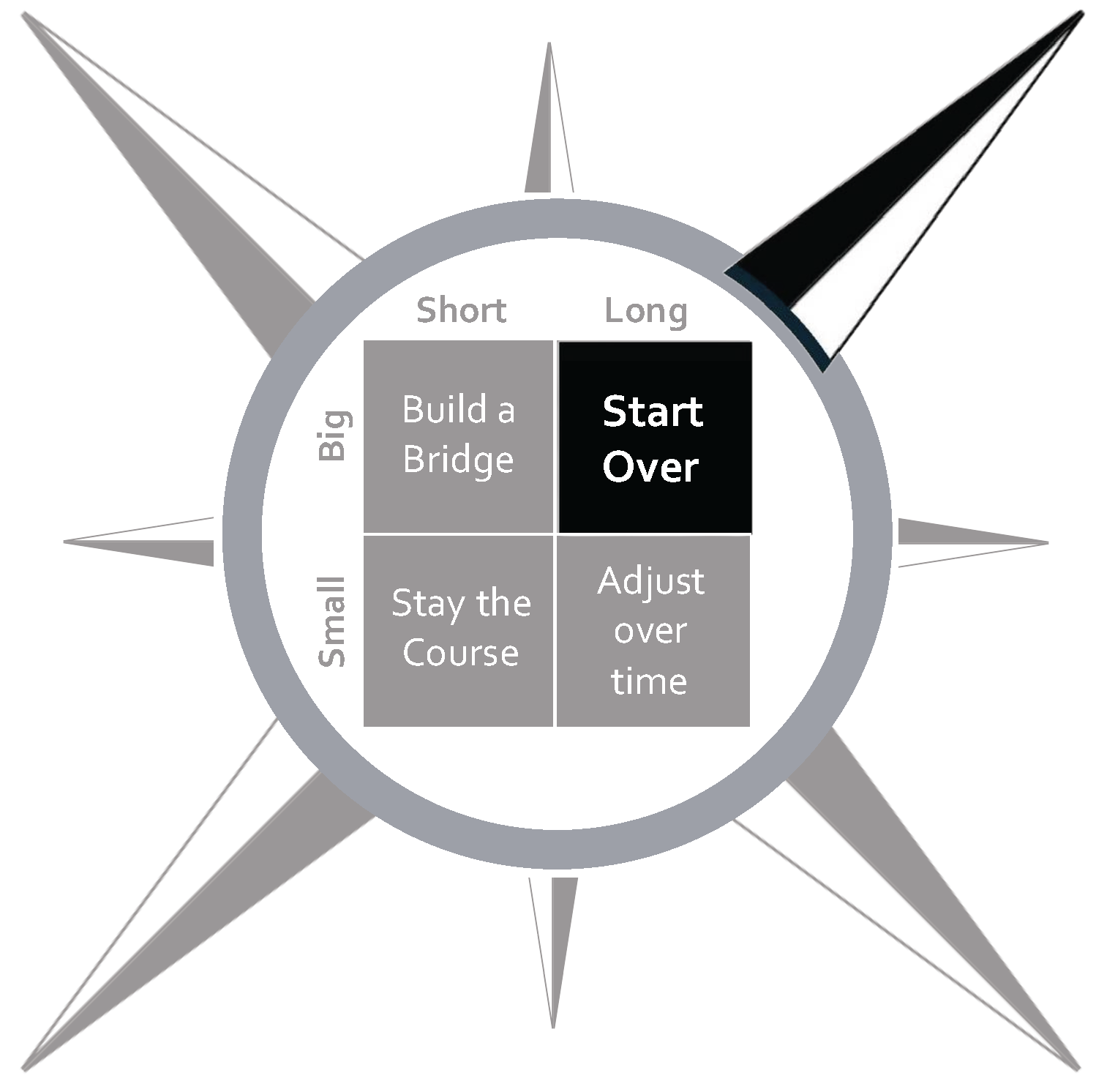

A good way to start is to ask two simple questions. First, are we facing big changes or small ones? Second, are these changes temporary or persistent? Put the answers together, and the path to problem-solving jumps right out.

Small Changes, Short Duration. These are the bumps in the road that we can usually handle by staying the course with careful monitoring.

Small Changes, Long Duration. These changes can’t be ignored, because problems only get bigger. But we have time to make adjustments and gradually get back on track.

Big Changes, Short Duration. We’re knocked off our feet, but we can see a way to get back up. Maybe a revenue stream has been interrupted but we are confident it’s coming back. Maybe we’ve experienced a natural disaster. Our job is to build a bridge to a well-defined and achievable future.

Big Changes, Long Duration. This is a whole different animal. Staying the course won’t work; time is not on our side; we don’t know where to build a bridge. Past assumptions and practices don’t work anymore, so we have to start thinking all over again.

How does Amherst look through this lens?

Big or Small?

I’ve been working on local issues for nearly fifty years, and have lived through many changes. But I have never seen anything like the upheaval we’re experiencing today. Here are just a few examples:

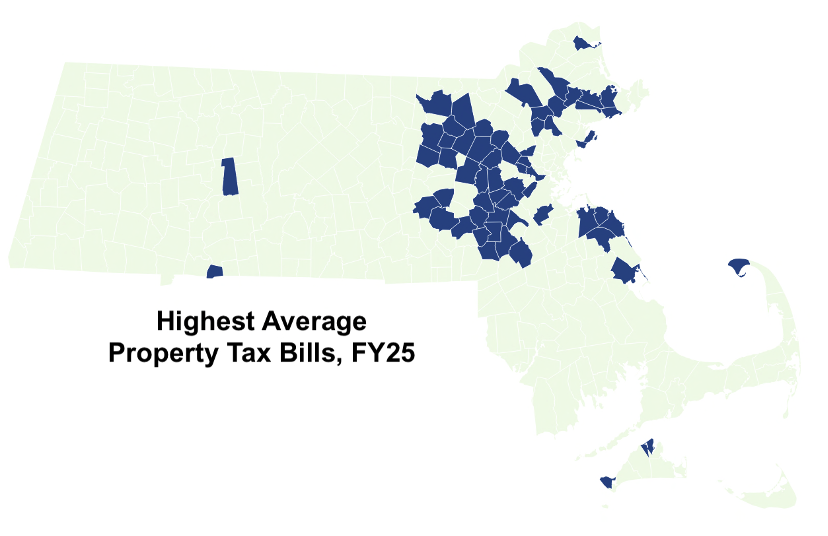

- Revenues and taxes. In 1990, when the dust from the passage of Proposition 2 1⁄2 had finally settled, the property tax was paying 35% of our bills and state aid was paying 22%. Today, that’s 58% and 16%. One result: since 2002, the average home’s tax bill has risen by 157%, twice as fast as inflation. No one west of Rte. 495 has higher average tax bills than Amherst (and Longmeadow).

- UMass. Since 2002 both UMass staffing and enrollment have grown by about 35%, the biggest jump since the Baby Boom years. This has impacted the community in many ways. For example, UMass added about 9,000 students during this period, but built only 3,000 new on-campus beds. And that hiring of staff surely put additional pressure on housing prices.

- Public school enrollment. Since 2002, our school-age population has fallen by 38%. At the current rate, in five years we will be educating half as many children as we once did. Other communities are experiencing enrollment changes, but nothing like this. Statewide, the decline has been less than 10% (and 61 communities saw enrollment growth). In fact, only one other community in Massachusetts has lost as many students as Amherst.

The list could go on and on. The point is simply to demonstrate that, if we’re trying to evaluate whether the changes we face are small or large, the answer is pretty clear.

What about duration?

First, these changes have been at work for a long time. Our revenue base has been eroding for half a century. Other trends have been building for decades. Looking ahead, can we see anything that might turn things around? The state shows no signs of greater generosity to communities like Amherst. We might find ways to broaden our tax base, but that would require time and a willingness to do things differently. The University is facing even more uncertainty than we are, and its troubles will undoubtedly ramify throughout the community. And school enrollments do not seem likely to rebound any time soon. Regional enrollment follows elementary trends in lockstep, so we know what to anticipate there for at least the next six years. And the U.S. birthrate continues to decline: the record for lowest birthrate in American history was broken three times in the past five years.

If we’re trying to imagine a sustainable financial future for our community — one that respects our values and reflects our priorities — then to me it’s clear we need to do some serious planning. We may not have been dealt a hand we like, but we’re obliged to play it as well as we can.

And that brings us to the third narrative.

Narrative #3: Wake Up and Smell the Coffee

We’re left with no real choice but to start over in our thinking. This is a path we might hope to avoid, except for one thing: it’s absolutely necessary. Denial, changing the subject, pointing fingers, questioning motives, and magical thinking are always popular. Yet they all delay the moment when we begin to work on our problem, thus ensuring that it will become bigger and more prolonged.

The vulnerability of this approach is the risk that we won’t pull it off, that we won’t be able to rise to the occasion and get a grip on the tiller. And that’s a legitimate concern. But I believe this is something our community is fully capable of. The risks of failing to try are much greater.

What does “smelling the coffee” involve? Here are some principles to think about:

- Start at the beginning. The overarching problem is that our revenue and our spending are out of sync. It’s essential that we construct a realistic scenario about what we’ll have to spend in the years ahead. (And as we do that, let’s remind ourselves that we are not helpless — more on that coming shortly.) But let’s resist trying to divide up the pie until we understand what’s coming out of the oven.

- Put everything on the table. So much of what we do today is a legacy of the past. We do not need to abandon our values and aspirations, but how we bring them to life demands a full and fresh look. Every piece of the puzzle demands scrutiny.

- Cooperate. Everything about our legacy budgeting system creates silos, not community. We suffer from a deficit of common understanding, and a surplus of narrow focus. As we set about reexamining our service and spending needs, let’s do it together.

- Open our eyes. If you found yourself saying, “Huh – I didn’t know that” at some point as you read this piece, you’re probably not alone. Our process is not well-equipped to provide insights and challenge assumptions. But there is plenty of useful information out there if we will only look for it.

We do not face a doomsday scenario. We have the resources to renew our community for the years ahead. But we don’t have time to waste squabbling around the edges. Let’s get going.

Bryan Harvey served as chair of the 2001-03 Amherst Charter Commission. He also served on the Amherst Finance Committee from 1981 to 1991, and on the Amherst Selectboard from 1991-2001. He is married to Town Councilor Lynn Griesemer. This post reflects only his own perspective.

Discover more from THE AMHERST CURRENT

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Bryan, absolutely brilliant and right on target. Irv Rhodes

LikeLike

But why is our per-pupil cost so much higher than other communities? Are our students qualitatively different from other places or from 25 years ago? Do we have a larger proportion of students with special needs? Are our teachers better paid? Do our schools offer a qualitatively different curriculum than other communities? Are our school buildings more expensive to maintain? Should we bring in DOGE to root out waste and fraud (just kidding!)?

LikeLike

Here’s an answer to some of your questions (from another Amherst Current article by Allison McDonald):

“The differences in per-pupil spending between districts are related primarily to the differences in the needs of the students enrolled. In Amherst, 49% of our students are “high needs” as defined by the state, that includes students with disabilities (22%), students whose families are economically disadvantaged (34%) and students learning English (14%). In the regional schools, 44% of students are “high needs.” Additionally, our districts’ staffing models, with small class sizes and low student-to-teacher ratios, our small schools, our family and student support programs, as well as staff pay and benefits, all contribute to higher per-pupil spending than some other districts.”

J Palmer Fox

LikeLike

These are excellent points. Do they adequately explain the difference in per-pupil costs? We need to think that through. One quick observation:

Yes, the Amherst high-needs population (weighted average of Amherst Elementary and Amherst-Pelham Regional) was 49% in the 2023-24 school year. It was also 49% in South Hadley, 44% in Northampton, 41% in East Longmeadow, and 55% in Easthampton. This pattern has changed from years past. The high needs population has risen across the board over the past decade, and each of these neighboring communities except Northampton has seen substantially greater growth than Amherst. This is one of the points of my piece: that we need to understand our situation today (and make our best estimate of the future).

The comparison of per-pupil costs was not to suggest that Amherst should try to match spending with our neighbors, but to indicate that Amherst provides an exceptional level of support to education.

LikeLike

Bob Rakoff, you echo my questions exactly. I do appreciate Bryan Harvey’s statistics, but I wonder why we spend so much more per pupil.

And thank you, Bryan, for that clear-thinking assessment.

LikeLike

Hi, Bob. These are exactly the kinds of questions we need to be exploring (except for the DOGE Part… .>

I’m going to dig into some of these in an upcoming post, and I hope we can keep asking (and trying to answer) important questions about everything we do as a community.

LikeLike

Is the Ritz Carleton library expansion part of Bryan’s conversation? His is a brilliant article, I pray folks are paying attention! Best regards,

Hilda Greenbaum

LikeLike

Are there other districts with a similarly high percentage of special needs students? How do they manage? Perhaps districts that face such challenges should get special consideration from the state?

LikeLike

Hi, Ernie. For a start, see my reply to Jay Fox, above.

LikeLike

Nice article Bryan. The graphic on big/small change and short/long duration to frame the optimal scale of the problem-solving approach was excellent, as was the municipal research you provided.

I like comparing Amherst to both nearby and state-wide communities to better understand our situation and learn what’s working for other communities. There’s no reason to reinvent the wheel if we don’t have to, but clearly Amherst is an outlier with regard to our school spending. You’ve made a good argument for option #3 “wake up and smell the coffee “as being the task at hand.

In the spirit of the “Hands Off” protests that are taking place today, I look forward to our town taking a “hands-on” approach to come up with a long-term solution to the school budget problem. We need to be bold yet honest with our situation.

I think Peter Demling’s 2-part article last Fall will be helpful to this end:

LikeLike

This analysis is excellent, and thorough in almost every area. Missing, however, is a direct call to seek more revenue from UMASS. The impact on our roads and other infrastructure by its students, faculty, staff, administration, contractors, and service providers dwarfs that of permanent residents. Yet they pay far less than would be the case if they were subject to property tax based on assessed valuation. Why has Amherst avoided publicly discussing this? There would be millions of dollars due if fairness was a criteria instead of acquiescing to the status quo. Why fear speaking truth to power?

LikeLike

Comment from Jan Wojcik:

I greatly appreciate your articles and although I no longer live in Amherst or Leverett I do try to follow what is going on with the town and school systems.

The article by Bryan Harvey on 4/4/25 caught my eye.

When he stated that the total expenditure per student was almost the highest in Amherst, I would like to point out that it is even higher in Great Barrington.

The Berkshire Hills Regional School District was paying over 29K when APRSD was paying 27.3K based on the DESE data.

We are having the same issues as you all are with declining enrollment and aging population facing a unsustainable tax levy from the school district, which comprises the towns of Great Barrington, Stockbridge and West Stockbridge.

We have an ancient HS that is too large and state is mandating that we replace it with another large HS that we can’t afford.

Thanks again for intelligent and insightful articles.

LikeLike

Bryan, excellent piece! Thanks from Northampton, also struggling with these issues. The approach you suggest is similar to what many of us who support adequately funding the Northampton Public Schools have been suggesting for over a year now. The circumstances cry out for a serious reconsideration of the use of financial resources to meet community priorities.

LikeLike