This is the second part of series on Amherst newspapers and blogs from 1977 to the present. Here’s a link to Part One.

By Nick Grabbe

Amherst news stories attracted national attention four times between 1997 and 2002, as many Americans heard about our town because of a canceled high school musical, criticism of the flag, odd police incidents, and a fake Emily Dickinson manuscript.

And three times over the next few years, newspapers revealed that men who worked with young people in Amherst had to resign because of sexual improprieties.

It was a time when most people still got most of their local news from newspapers. And as the 1980s ended, the Amherst Bulletin was a successful weekly newspaper, with deep roots in the community and lots of advertising that paid for a large staff and free delivery through the mail.

But the Bulletin had a fundamental problem, and the solution to that problem, though perhaps inevitable, contributed to its ultimate decline.

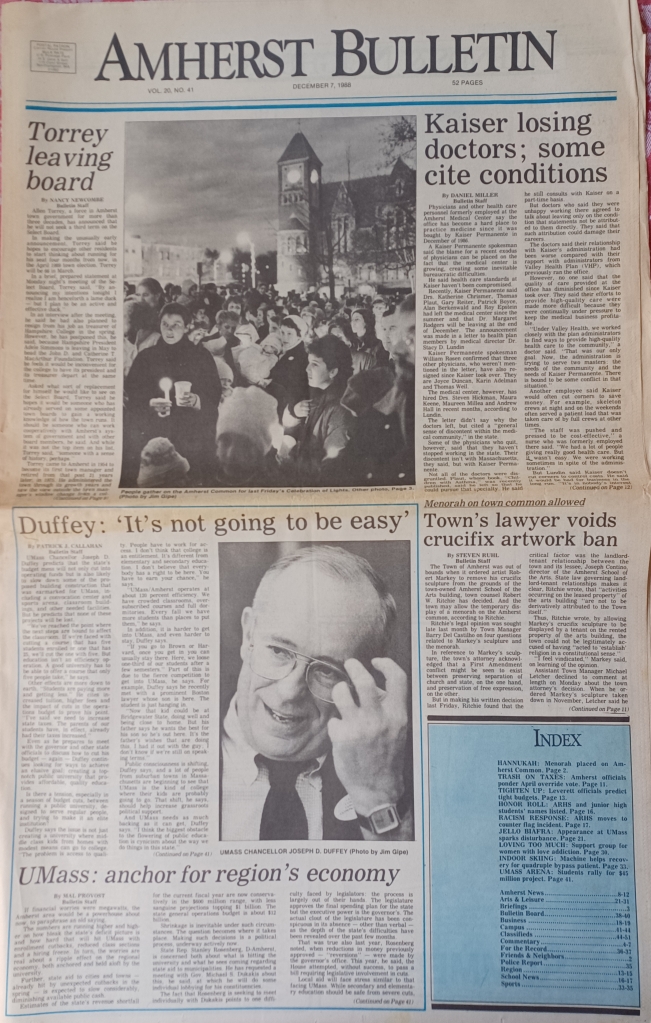

I had been the editor of the Bulletin since 1980. In 1987 and ’88, the paper was sometimes as fat as 52 pages, five and a half times bigger than today’s Bulletin. It had a full-time staff of 11 and a busy office downtown. An independent survey found that the Bulletin’s readers “exhibit remarkably strong loyalty to their weekly.”

The Bulletin had three reporters who lived in Amherst and had extensive experience writing about Town government and the schools. It had sections devoted to Amherst sports and to news from the regional towns and campuses. There was a robust commentary page with regular columnists and lots of letters. Local people wrote about Amherst’s history, gardening, fitness, food, music and movies.

But there was a problem. The Bulletin and the Daily Hampshire Gazette, based in Northampton, were owned by the same company. The two papers had separate Amherst staffs, but we worked in the same office and were often in competition with each other for stories. There were often two reporters at Select Board meetings, one from each paper, and two reporters and two photographers at high school football games. When ad revenue declined in 1990-91, this unusual duplication of effort became untenable.

Some Gazette employees in Northampton felt, justifiably, that the free Bulletin limited paid circulation of the daily paper in Amherst. In February 1991, the two papers merged their news-gathering operations. This change happened the same week as another news story that brought Amherst national notoriety: Gregory Levey died after setting himself on fire on the town common in an antiwar protest.

It made sense for the two papers to stop competing with each other, but the 1990s saw a gradual diminishing of the Bulletin’s independence and impact. News stories now had to come out first in the daily Gazette, leaving the Bulletin trying to approach issues differently while using the same reporters. The Bulletin frequently published features on the front page that were not in the Gazette, but increasingly, the news stories were the same in both papers.

In the early 1990s, the Gazette and Bulletin covered tax overrides, instructional grouping in the Amherst schools, bad blood on the Select Board, town-gown conflicts and a proposal to cut the number of streetlights. With echoes today, there was a successful plan for a $3.2 million Jones Library renovation and expansion and an unsuccessful plan for a $8.9 million new elementary school.

Two Amherst natives who would become influential in town wrote regular columns for the Bulletin. Larry Kelley railed about the Cherry Hill Golf Course purchase and Town-funded recreation programs, while Meg Gage proposed turning the junior high into a middle school. Well-known writers such as Julius Lester and Howard Ziff wrote commentaries.

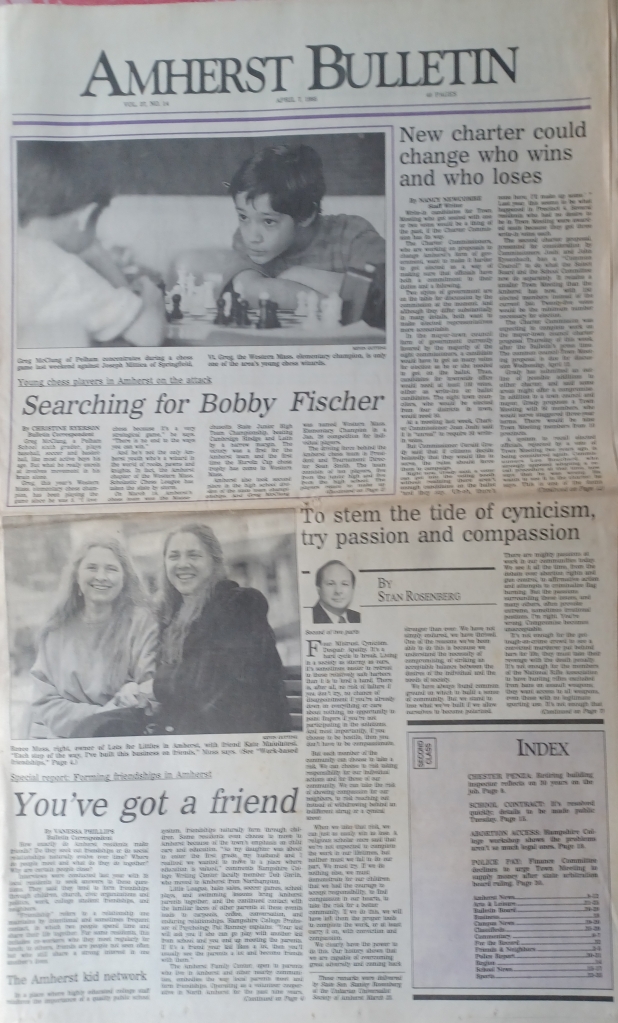

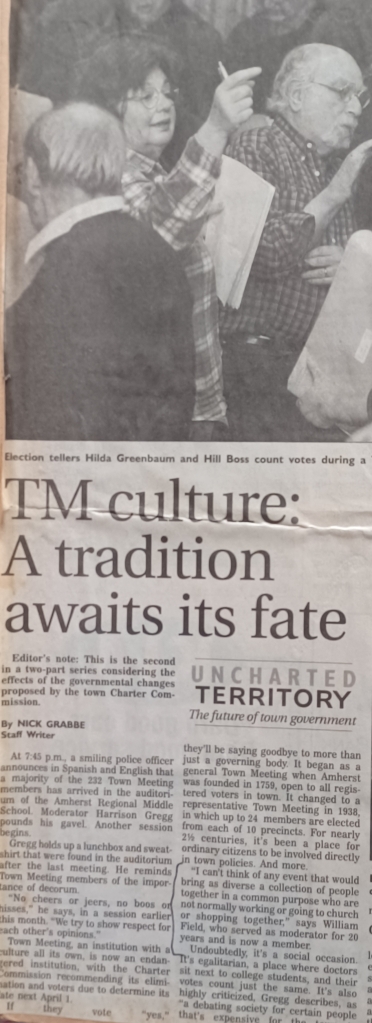

The Gazette and Bulletin extensively covered the first of Amherst’s three charter commissions, and the rejection in 1994 of its proposal to create a seven-member town council, with one acting as a mayor, but to keep a smaller Town Meeting. A group called Amherst Citizens for Responsible Government supported the proposed change in government, and helped defeat tax overrides for the regional schools, expansion of the high school, and renovation of Town Hall.

During the 1990s, the newspapers covered numerous Amherst controversies: the removal of a Christmas tree from the Jones Library, mold and sickness at Fort River School, efforts to broaden the tax base, banners with political messages over South Pleasant Street, and a photo exhibit in the elementary schools about non-traditional families called “Love Makes a Family.”

The biggest political battle of the 1990s was over building a parking garage. The Bulletin published a chart of pros and cons of three sites: Boltwood Walk, behind CVS, and Amity Street. There were six Town Meeting sessions in 1997 just on the garage issue, which the Bulletin called “Amherst’s longest-running soap opera.” Town Meeting rejected a plan for a larger garage at Boltwood Walk, and a compromise was finally agreed on for a smaller structure, the one you see there today.

The newspapers also covered vandalism at a typewriter store that was seen as racist and inspired a group called Not In Our Town. There was a debate over whether posters on bus shelters and light poles created a cosmopolitan atmosphere or a sloppy appearance. Dan Lombardo at the Jones Library found that a newly discovered manuscript by Emily Dickinson was actually the work of a master forger, a story that brought international attention to Amherst.

In 1997, a UMass student, apparently drunk, died after he fell through a greenhouse roof on campus. The police were responding regularly to gatherings of hundreds of students, many of them drunk, outside Antonio’s and on Hobart Lane. Longtime residents living near the campus complained about late-night noise. The Gazette frequently reported incidents of student misbehavior – and some in Amherst wondered if it exaggerated the extent of the problem. In 1998, the Gazette produced a special section called “One Weekend in Amherst” about student drinking.

Smoking also became an issue. The Bulletin conducted a sting, giving two underage youths money and instructing them to try to buy cigarettes at 21 stores. The paper then listed the names of the 18 stores that did not bother asking them for IDs. The Board of Health banned smoking in all Amherst bars, a move that was controversial at the time but within a few years was adopted widely in Massachusetts.

In 1999, ARHS canceled a planned production of “West Side Story,” and the resulting controversy was picked up by the international press. While Puerto Rican students and some parents maintained that the musical promoted harmful stereotypes, others called the cancellation political correctness run amok.

I stepped down as editor of the Amherst Bulletin in 1999 and became a writer for both papers, whose staffs were by then firmly integrated. For the first time, one person was responsible for Amherst coverage in both papers. And, for the first time, the editor of the Bulletin did not live in Amherst and, based in Northampton, rarely came here. Some of these Amherst editors were capable, but their unfamiliarity with the town popped up on occasion, such as when a headline referred to Select Board member Hill Boss as “Hill.”

By the turn of the century, the long, slow decline of newspapers nationwide had begun, as the Internet expanded the options for receiving information and cut into everyone’s reading time. Local newspapers suffered the most.

In early 2002, the Gazette and Bulletin announced a reduction in staffing by the equivalent of 11 full-time positions. The Gazette’s circulation had started a long decline, the company’s profit margin had been cut in half, and advertising was down by 7 percent. Craig’s List undercut the once-profitable Classified ads.

On Sept. 11, 2001, shortly after planes flew into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the newspapers sprang into action, covering the reactions to the terrorist attacks. About 14 hours before that unforgettable moment, the Select Board had had a vigorous debate over the placement of 29 American flags on downtown light poles. The newspapers reported that UMass physics professor Jennie Traschen told the Select Board that some see the flag as “a symbol of terrorism and death and fear and destruction and oppression.” Her unfortunately timed remarks were reported by national news outlets. By the end of 2001 she had received 1,500 emails, most of them critical and many of them obscene.

The town manager ordered the flags taken down a few days after Sept. 11, but the Select Board tangled with Larry Kelley over the timing and extent of the flag display for several years.

Amazingly, three men who worked with young people in Amherst resigned because of sexual improprieties in the early 2000s. The Gazette reported that the ARHS principal was alleged to have asked a male 9th grader to expose a nipple, and the Town’s youth sports director left after officials found that he wrote sexually oriented e-mails using boys’ names and transmitted them to his home computer. The director of the Amherst Boys and Girls Club was arrested for possession of child pornography.

The early 2000s also saw a lawsuit by 27 Orchard Valley residents that didn’t succeed in blocking an affordable housing complex, and a campaign to revive the Amherst Cinema that did succeed. The price of Amherst house lots topped $100,000.

Criticism of Town Meeting continued. In the spring of 2001, it lasted 12 nights, and in 2002 one session got through only two articles of a 45-article warrant. Turnout in the local election dipped to 7.7 percent.

Voters created a second Charter Commission in 2001, and its nine members met more than 50 times. Seven of the members supported its proposal to replace Town Meeting with a nine-member council, with both an elected mayor and a manager. In 2003, voters rejected this plan by only 14 votes, and in 2005 they rejected it again, by a wider margin.

Scott Merzbach started writing the Bulletin police log in 1997, and it was a surprise hit with readers. It was also the subject of a four-page article in Harper’s magazine in 2002 called “Gone When Police Got There.” A Leverett man collected quirky items from the police log, calling them “found poetry,” and collected them in a book, describing incidents such as a frozen turkey plunked in the middle of North Pleasant Street and a man licking the pavement on Main Street.

Amherst’s distinctiveness was, once again, publicized around the country.

Next in this series: As newspapers serving Amherst continued to struggle, 10 blogs and web sites started providing residents with news and views.

Really enjoying this series!

LikeLike

[…] This is the third in a series of posts about Amherst journalism from 1977 to the present. Here are links to Part One (1977-1989) and Part Two (1988-2003). […]

LikeLike